TJORITJA (West MacDonnell Ranges) – Camping Traditions

TJORITJA (West MacDonnell Ranges): A convergence of camping traditions

Story by Matt Sykes.

The author acknowledges the Arrernte people and their ancestors as the traditional owners of Tjoritja (the West MacDonnell Ranges) where this article is set.

Warning: This story contains images of Aboriginal people who have passed away.

Lounging around the fire pit after a day trekking the Pinta – Ormiston Creek camp.

(Photo courtesy of guest David Slater, 2015).

The tradition of camping in Tjoritja goes back tens of thousands of years (pronounced Choritja by Spencer & Gillen (1)). Although Arrernte and non-Aboriginal peoples’ relationship with campsite settings like Ormiston Creek (pictured above) differ, the magnetic attraction of these places is the same. As a company, Trek Larapinta prides itself on low impact, site-specific standing camps which are dismantled in the off-season leaving no trace. In many cases, our net environmental impact could be argued to be positive because of the clearing of weeds like Buffel Grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) that we undertake and the “watering” of trees. In the same way that Arrernte people use bush materials and careful consideration of their environment, we also try to blend our camps into their surrounds. This blog post provides a snapshot of the evolution of camping within the broader region of the Larapinta Trail.

Introduction of European camping traditions

We often talk about the introduction of foreign plants, animals and people to Australia, but it’s also interesting to contemplate the introduction of certain cultural traditions, like camping. What’s even more interesting is when you start to see the environment shape those foreign traditions. For example, the birth of the “swag” – a rolled up bed carried on one’s back – became a vital tool for itinerant European men roaming the land in search of work in the 1800s, as typified by McCubbin’s painting ‘Down on his luck’. Not only did the Australian environment (geographic, social, economic and political) shape this camping icon, the swag has become a cornerstone of Australian identity. Our unofficial national anthem ‘Waltzing Matilda’ by Banjo Patterson sees a swagman as its ill-fated hero.

But instead of discussing European camping traditions in Australia, this article will acknowledge Tjoritja’s original camping traditions and track how the two are converging.

‘Down on his luck’, Frederick McCubbin (1889) (2)

The evolution of Arrernte camp architecture

Without accessible records of Arrernte culture before European arrival, we are left to track the evolution of their camping traditions through the diary entries and photographs of early European explorers. In 1860, John McDouall Stuart, ‘with two other men and a dozen horses … spent three days finding their way through the MacDonnell Ranges’. (3) He was the first European to venture into the region. However, it wasn’t until 1877 when the Hermannsburg Mission was established and the Lutheran missionaries began living with Arrernte people that we first start to get insights into traditional camp life. Most notably Carl Strehlow (1871-1922) documented Arrernte language, cultural practices and ceremonial artefacts in more detail than any person before him and since. His work now forms the foundations of the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs, much of which is not publicly accessible.

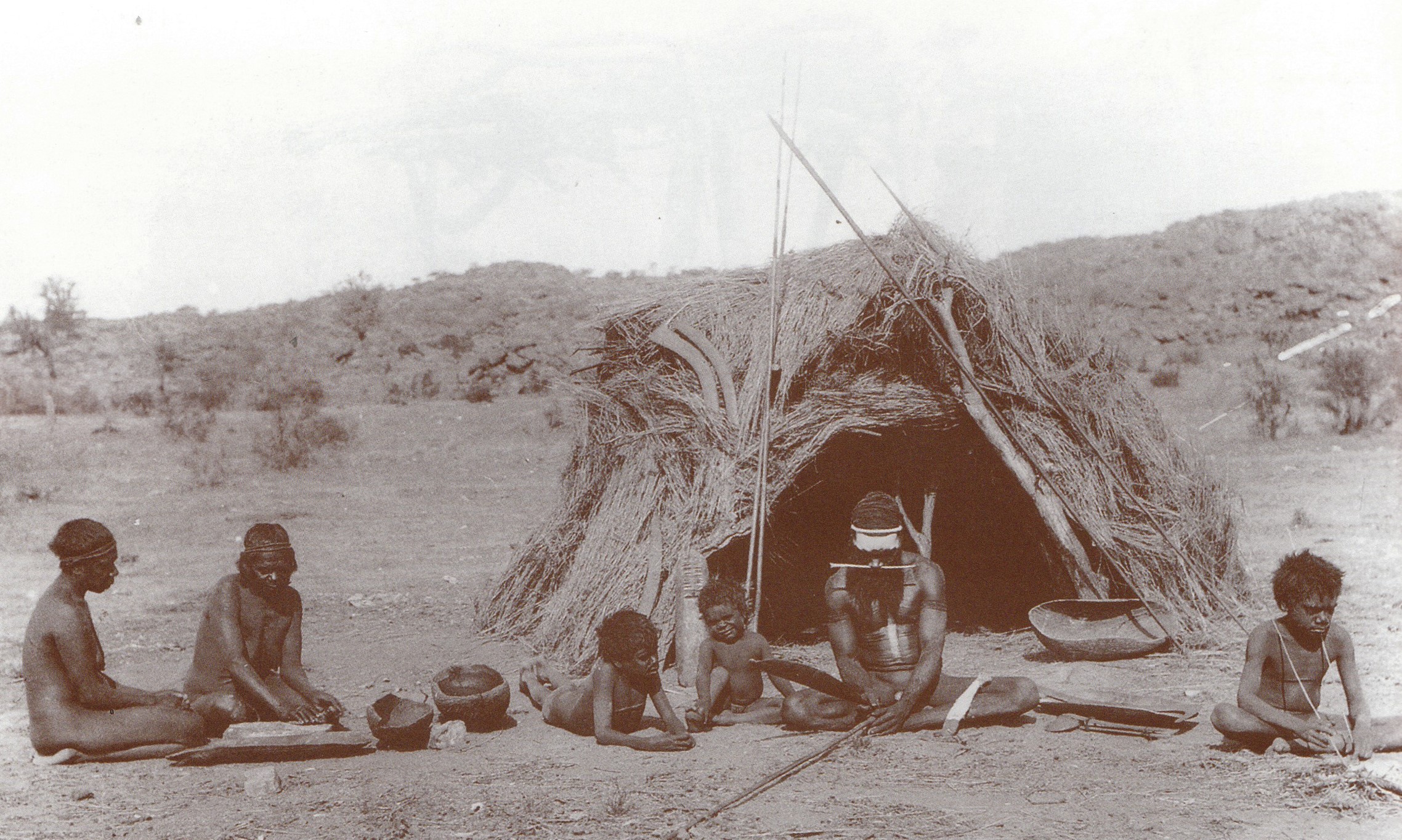

Spencer and Gillen were explorers of the same period. Paul Memmott describes one of their photographs in his book ‘Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia’

‘An Arrernte domiciliary group photographed in 1896 near the present-day site of Alice Springs, in front of a domed shelter constructed of heavy limbs and clad with grass. This is probably a polygamous family, comprising a man with two wives and their respective children. The man is scraping back a spear shaft with a stone adze while the women are grinding seeds to make cakes. The boy is making his own toy spear. Photograph by Spencer & Gillen from Museum Victoria and SA Museum.’ (4)

This is likely to be a staged scene but you still get an insight into the materials and construction methods that the Arrernte adapted from their arid environment. Another image, below, taken a generation later by Pastor Reidel (another Hermannsburg missionary) shows a camp architecture rapidly evolving.

Memmott describes,

‘Lutheran Mission Village on the outskirts of Alice Springs, October 1923. Grass-thatching techniques had been adopted by the Western Arrernte people for their semi-sedentary mission lifestyle. Photograph by Pastor J. Riedel. Image courtesy of Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Lutheran collection (image number N6492.27).’ (4)

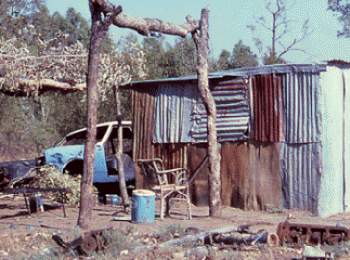

The next transition towards sedentary living can be seen in the shaping of town camps on the fringe of Alice Springs. In 1989, Paul Memmott ‘was commissioned by Tangentyere Council to carry out a study of Aboriginal social problems in four Alice Springs Town Camps … and produce Social Planning Reports on each of them.’ (5)

In the camp architecture you see a partial departure from traditional materials and construction techniques. Acknowledging the very real social issues associated with these changes, you can still see the richness of the Arrernte peoples’ camping tradition. For example, in the left hand side of photograph below, notice the piling of foliage on the shade shelter and the structure’s timber supports. These are the same fundamental techniques employed by their ancestors.

A question arises, if Arrernte town camp architecture sits somewhere between Aboriginal and European traditions, what can non-Aboriginal campers learn from the ways they have blended the two?

Alice Springs Town Camp, c1989 (5)

Converging traditions, one environment

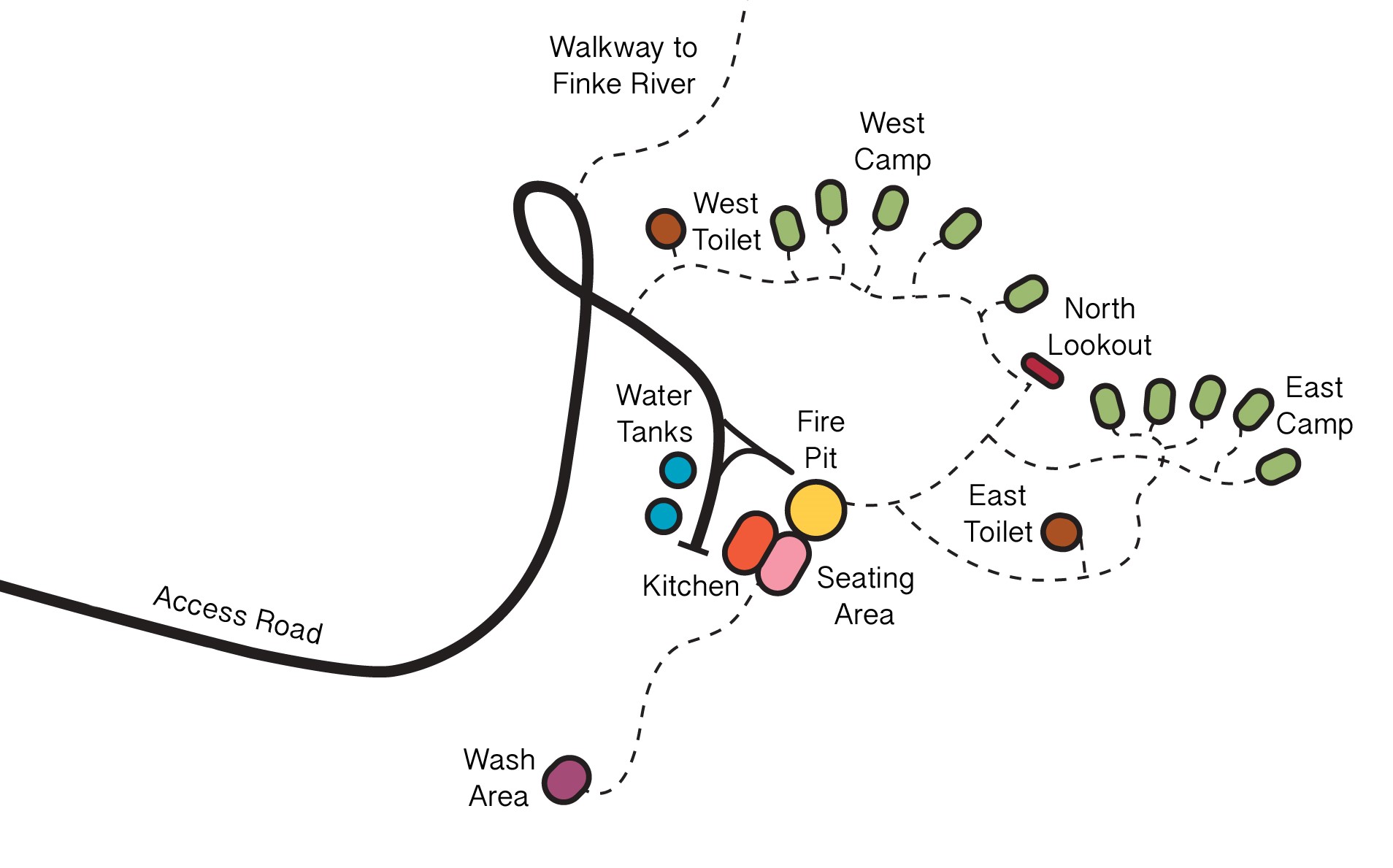

The above question is something that we’re considering in the design of Trek Larapinta’s newest standing camp. Careful attention is being paid as we work with the Central Land Council and NT Parks & Wildlife in the camp’s siting. Like our existing camps, paths and structures are being positioned to fit in amongst the existing immediate landscape, whilst connecting to views of the epic surrounds, including stunning sunset views of Rwetyepme (Mount Sonder). We are seeking to use local organic materials (gravel, stone, timber) alongside canvas tents and tarps, as well as modern kitchen appliances, solar technology and water storage.

The goal is not to copy Arrernte architects. That is not necessary or desirable. We have other materials and construction techniques at our disposal, which have been proven through their own heritage. Rather we are responding to the same environments that the desert’s first people have responded to. It is the environment that drives us, and so we as the current generation of Tjoritja campers should listen to its subtleties and adapt, in our own way.

Pioneer Creek camp, our canvas tents resemble traditional Arrernte dome shelters.

Masterplan for Trek Larapinta’s newest bush camp, Design by Matt Sykes.

Links

http://hermannsburg.com.au/

http://www.magnt.net.au/#!strehlow-research-centre/c125s

http://opbg.com.au/

http://www.aerc.uq.edu.au/

References

(1) Strehlow, J. (2011) ‘The Tale of Frieda Keysser, Frieda Keysser and Carl Strehlow: An Historical Biography’, Volume 1: 1875-1910, Wild Cat Press, London.

(2) National Gallery of Victoria (2016) Image of F. McCubbin’s painting ‘Down on his luck’. Accessed on April 27 2016 from http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/australianimpressionism/education/insights_national.html

(3) Latz, P. (2014) ‘Blind Moses’ Self-published, Alice Springs.

(4) Memmott, P. (2007) ‘Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia’ University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, QLD.

(5) The University of Queensland (2016) Photo of Alice Springs town camp. Accessed April 27 2016 from http://www.aerc.uq.edu.au/tangentyere-council-alice-springs-town-camps